|

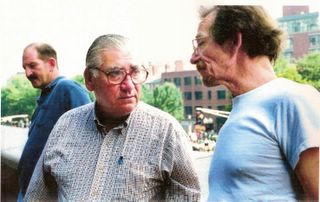

| George Mendoza on the job at the shelter. |

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 8/28/2003

For the past 12 years, when doctors and other professionals failed, George Mendoza found a way to gain the trust and help heal the wounds of some of the nation's most alienated veterans, many still struggling to "return home" from the Vietnam War.

Now, the 64-year-old is out of a job. Administrators at the New England Shelter for Homeless Veterans, where Mendoza founded a nationally acclaimed post-traumatic stress disorder program, laid him off earlier this month, saying they could no longer afford his $49,000-a-year salary.

Mendoza and several of the nation's top post-traumatic stress doctors and therapists, as well as more than a dozen veterans still in the program, warned shelter officials that abruptly taking him away from his patients could have potentially deadly consequences.

"I tried to explain that you can't just leave PTSD clients," said Mendoza, who said administrators initially pressured him to retire. "They need time. They need a transition."

Administrators declined to comment in detail about Mendoza's departure, but said they eliminated his position to save money - a vital task for a shelter that has experienced severe financial problems over the past year. The program will continue, with a doctor, psychologist, and caseworker caring for patients.

Approached in front of the shelter's Court Street building in downtown Boston last week, chief executive Diane Gilbert, said: "We don't discuss personnel actions."

The shelter's move, which Mendoza said gave him only two weeks to prepare his patients for his departure, prompted doctors in the field to write Gilbert and board members, asking them to reconsider their decision.

"I want to make my professional opinion absolutely clear:

Abrupt termination of his program is likely to result in severe and possibly fatal harm to veterans in his program or to others," wrote Dr. Jonathan Shay, a psychiatrist at Boston's VA Outpatient Clinic and a nationally recognized specialist who helped draft the Pentagon's guidelines for treating PTSD. "Another counselor cannot replace him in this role, regardless of the person's credentials."

Abrupt termination of his program is likely to result in severe and possibly fatal harm to veterans in his program or to others," wrote Dr. Jonathan Shay, a psychiatrist at Boston's VA Outpatient Clinic and a nationally recognized specialist who helped draft the Pentagon's guidelines for treating PTSD. "Another counselor cannot replace him in this role, regardless of the person's credentials."Dr. John Woodall, director of Harvard's Resilient Responses to Social Crisis Working Group, warned the board in a letter that it risked legal liability for "patient abandonment."

"If a bad outcome occurs, a suicide or a homicide or assault, the liability is much greater," Woodall wrote. "Despite what personal, political, fiscal or administrative problems may exist, George Mendoza must be involved in this transition to closure."

Neither Shay nor Woodall has received a response from the shelter.

Earlier this summer, administrators announced the elimination of 27 jobs, saying the cuts would save $700,000 and ensure the shelter would remain able to house and feed hundreds of veterans every night.

In announcing the cuts, which came several months after the state briefly took over the shelter's books, Gilbert said, "We have been guided by one unwavering principle: Our core services must remain available to every veteran in need."

But some patients, clinicians, and former officials in the veterans department argue the loss of Mendoza will affect core services.

"It seems like the shelter forgot the reason it's there," said Dr. Isaias Sepulveda, a psychiatrist at the Brockton Veterans Administration Medical Center who sees patients at the shelter.

"His services are desperately needed," said Thomas J. Hudner Jr., former commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Veterans Services, which oversees some $2 million the state provides the shelter. "There has to be a continuum of counseling for PTSD cases. To be left in the middle of treatment, I think, would set them back quite a bit."

A short man with a potbelly, Mendoza never served in Vietnam. He isn't a doctor or a trained psychologist. Yet over the past decade he developed a reputation for breaking walls others found impenetrable. Though he trained with PTSD clinicians at the University of Massachusetts in Boston, his primary credentials, he said, come from surviving the so-called "Dirty War" in Argentina, which he escaped in 1983 after watching many of his relatives, friends, and colleagues die.

When the shelter made him its first employee in 1991, he created "the bunker," a novel approach to treating PTSD patients - and the first such program for homeless veterans. It's a place where veterans can hang around all day, talk to caseworkers at any time, and take part in therapy programs.

The main reason it worked: "It's about love," Mendoza said. "Love is one of the most powerful tools. If you don't love them, you can't do the job."

The affection goes both ways.

In interviews with more than a dozen of some 25 clients Mendoza treated before being laid off, many described him as a father. "Papa George is my mother, father, brother, and girlfriend all in one," said Curtis Calvin, 58, a former Army Ranger in the program since June. "He understands."

Another Vietnam vet, Billy Dyson, said he lived like a hermit for the past 30 years in "the bush" in New Zealand, struggling with flashbacks. When he heard about Mendoza's program, he saved enough money to buy a plane ticket to Boston. Now, the 57-year-old former soldier said: "George gave me back my life again, and all of a sudden, I feel betrayed, like the shelter ripped out the heart and soul of the program. It's a raw deal."

Others are just scared. David Nelson, a 53-year-old former sergeant, said: "Without George, I worry what I may do to myself, or others. I'm deeply concerned about my reactions. I feel like I could lose control of myself, that my anger might act out."

Though Mendoza has been out of a job nearly two weeks, he hasn't ended the relationship with "his men."

All have his cellphone number, and they continue to call him. He still hangs around the shelter almost every day, walking the streets to keep his veterans off them.

"This is not about me," Mendoza said. "I don't really need the job. It's about them."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe