By David Abel | Globe Staff | 8/10/2005

Over the past three decades, by his count, Bill Ilott molested 19 children, some as young as 13.

Police caught the former Army drill sergeant raised in Canton only once, in 1999, and he pleaded guilty to drugging and molesting four children while working as a tutor on Cape Cod.

The former alter boy, who graduated from Xaverian Brothers High School in Westwood, served three years in jail and three years of probation for his crimes, an addiction he likens to alcoholism.

Since then, like many other Level 3 sex offenders, a category the state uses to define those with a “high risk” of committing future sex crimes, the 50-year-old with thick, boxy glasses and a master’s degree has been homeless and unsuccessfully searching for a job in Boston.

“I was rescued rather than arrested, rescued from my addictions,” said Ilott, who lives in a city shelter and has desperately sought a job. “Boredom is my biggest killer. I need to use my brain. I think there’s more meant for me in the world than prison. It would be very sad if I ended up going back.”

It’s a fate he arguably deserves.

But the tall, balding man’s plight also presents a problem for the community: Sex offenders without work and housing are more likely to end up back in jail, research shows, often for the same kinds of crimes. A 2000 study cited by the US Justice Department’s Center for Sex Offender Management, for example, found unemployed sex offenders are 37 percent more likely than sex offenders with stable jobs to be convicted of a new crime.

The twin troubles for sex offenders trying to return to mainstream society – homelessness and unemployment – were exacerbated a year ago this August, when the Supreme Judicial Court ruled that the state could post the names, addresses, and photos of Level 3 sex offenders on a public Web site, offenders, social workers, and specialists in the field say. Over the past year, the site (www.mass.gov/sorb), which lists nearly 1,500 Level 3 offenders, has received millions of hits, more than 230,000 just in June, or nearly 8,000 a day.

Of 86 Level 3 offenders listed on the online registry as living in Boston this month, only 29 percent listed having work addresses – though it’s not clear whether they still had jobs – and at least 50 percent of those not in violation of the law listed their home addresses as easily identifiable city homeless shelters, such as the Pine Street Inn and the New England Shelter for Homeless Veterans. The registry didn’t list addresses of 14 sex offenders in violation of the law.

Like the other Level 3 offenders she treats, Ilott’s psychiatrist at the VA Clinic on Causeway Street said she’s “very concerned” about the long-term effects of homelessness and unemployment on her patients – none of whom have jobs and some of whom have been fired in the past year after employers discovered their photos online.

“The less you have to lose, the more you’re willing to squander,” said the psychiatrist, who asked not to be identified because she counsels other sex offenders. “Bill has been very demoralized, and he’s stuck. He can’t get out of where he is unless he gets a job. He’s a guy with a master’s degree who can’t find a job doing very basic stuff, and the question is: What’s keeping him from re-offending? At this point, what does he have to lose?”

STATE OFFICIALS ACKNOWLEDGE the problems of homelessness and unemployment, which affect many ex-cons, but no more than violent criminals such as sex offenders. Last fall, the Executive Office of Public Safety opened eight “reentry centers” throughout Massachusetts, including one in Mattapan, to help sex offenders register in their new communities and other ex-cons find work, housing, and treatment.

The problem, they say, has contributed to the nation’s high recidivism rates: Of about 600,000 inmates leaving jails and prisons around the country, police expect to re-arrest about two-thirds within three years. In Massachusetts, where about 20,000 inmates are released every year, state officials say prosecutors will convict nearly half of another crime in the same time.

“Successful employment and housing are two of the most major barriers to successful reentry,” said Maureen Walsh, chairman of the Massachusetts Parole Board, who noted the state’s new reentry centers have had limited success in helping certain ex-cons find jobs. “There’s no question – it’s absolutely difficult for violent offenders to find work.”

No statistics are available to reflect the impact of the registry on sex offenders.

But even if it has affected their ability to find work and housing, officials at the Massachusetts Sex Offender Registry Board say it’s wrong to blame the law, which requires that the state’s 9,000 sex offenders now out of prison keep their home and work addresses current with police for the rest of their lives. The state now also requires many Level 3 offenders leaving prison to wear electronic ankle bracelets, so officials can monitor their movement.

“The difficulty in finding employment is directly associated by the courts in recent decisions with society's repulsion of these terrible crimes, not the factual posting of that criminal information,” said Charles McDonald, a spokesman for the board. “Any possible adverse consequences that may befall a sex offender must give way to the legitimate concerns of public safety.”

Though he said the board favors Level 3 offenders finding work and housing, McDonald cited a 1994 federal court decision to underscore that the problems sex offenders experience after leaving jail aren’t just the result of having their photos published online: “Individuals may lose their jobs or be foreclosed from serving in future professions; their marriages are destroyed; they may be plunged into poverty .... Virtually all individuals who are convicted of serious crimes suffer humiliation and shame, and many may be ostracized by their communities.”

But even those who strongly support the registry say they worry the system now so isolates the state’s most dangerous sex offenders that it may be more likely they’ll end up back in prison.

Instead of making it more difficult for them to find work and homes, the state should provide more supervision, in some cases life-time parole, counseling, mandatory jail sentences for those who violate current laws, and much longer prison terms for sex offenders who commit future sex crimes, said Laurie Myers, president of Voices of Involved Citizens Encouraging Safety, a Chelmsford-based victims-rights advocacy group.

“Once they’ve done their time, they’ve done their time,” Myers said. “After, they deserve a normal life. If they’re going to return to our communities – and they do – they need jobs and somewhere to live.”

It’s a myth that sex offenders are condemned to repeat their crimes, say advocates and specialists, who note sex offenders are actually less likely than other ex-cons to be arrested for another crime.

A 2003 study released by the US Justice Department’s Bureau of Justice Statistics found little more than 5 percent of sex offenders had been rearrested for another sex crime within three years of leaving prison – a number, however, that doesn’t reflect the many victims who, because of shame or fear, don’t report the crimes. Still, overall, the study found sex offenders are 25 percent less likely than other non-sex offenders to be rearrested for any crime.

Because sustained counseling and a conviction to return to a normal life can succeed, some criminologists say the state must do more to put sex offenders on a better path, one that doesn’t involve unemployment and homelessness.

“The question is: Are we pushing them back into a life of crime, are we helping produce monsters?” said Jack Levin, director of the Brudnick Center on Violence and Conflict at Northeastern University. “It’s in our benefit to treat them in a humane way. Otherwise, their suffering will become our suffering.”

Levin – who argues the online registry does little more than make the community feel safe – says the state should do significantly more to help first-time offenders. But once sex offenders strike again, he says, they should be jailed for life.

“The rule for habitual rapists and child molesters should be: Two strikes and you're never out again,” he wrote in a recent essay in the Globe.

STROKING THE VIRGIN MARY AMULET dangling from his neck, Bill Ilott says he understands the consequences of his actions – that he has caused untold pain to his victims – and agrees with society’s efforts to keep close tabs on sex offenders.

Like most pedophiles,

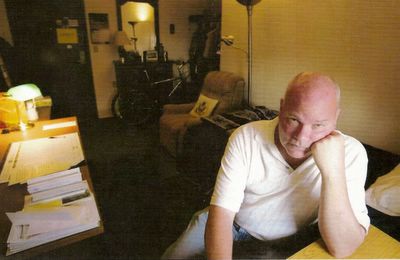

Ilott hasn’t sought publicity, and he wrestled with whether to speak on the record. A gap-toothed man with a sharp wit and contagious laugh, he agreed because, after three years searching for a job and living in city shelters, he has nothing to lose, he says. He also wants policymakers to understand the challenges he and other sex offenders face while trying to resume lives as law-abiding, tax-paying state residents.

Ilott hasn’t sought publicity, and he wrestled with whether to speak on the record. A gap-toothed man with a sharp wit and contagious laugh, he agreed because, after three years searching for a job and living in city shelters, he has nothing to lose, he says. He also wants policymakers to understand the challenges he and other sex offenders face while trying to resume lives as law-abiding, tax-paying state residents.The most immediate obstacle has been overcoming the desire to have sex with boys, which for him and other pedophiles is an impulse as strong as the biological drive of any adult who longs for sex. He compares the challenge to maintaining a diet during a Thanksgiving dinner. The best solution – in addition to therapy and the mood-controlling lithium he takes everyday now – is avoiding boys without supervision, a dangerous situation that he says makes his knees weak.

“It’s a biological urge you can’t will away – it’s with you forever,” Ilott said during an interview in the cramped room where he’s staying at the St. Francis House. “I’ve thought about the desire like an alcoholic thinks about a drink.”

His psychiatrist says as much as Ilott and other sex offenders may understand the pain their crimes have caused, they have “empathy switches” they can turn off. But sustained therapy can significantly reduce that likelihood – six times more than for those who don’t receive treatment, she says.

“They suffer from a sexual disorder, in which their object of desire is abnormal,” she said. “The balance from keeping him re-offending is controlling the drive and having good reasons not to re-offend.”

Finding such reasons can be the biggest challenge, particularly when returning to prison guarantees a roof over a sex offender’s head, a bed, regular meals, even their laundry done for them.

It’s not just the stigma of their crimes that keep them from finding work; parole requirements bar most Level 3 offenders from holding nearly any service-oriented job where they might interact with the public.

Jobs at anywhere from McDonald’s to CVS, for example, are off-limits because sex offenders may be in close proximity to children. So are positions as a waiter, security guard, taxi driver, or working at a hospital, school, university, or anywhere near a day-care center. Moreover, their odds of landing a job plummet with any employer who does a criminal-record check.

FOR ILOTT, A 10-YEAR ARMY VETERAN whose resume boasts a master’s in public administration and a bachelor’s in social work from Georgia State University in Atlanta, the limited prospects have forced him to use his body as a test subject. He says he has undergone 7 MRI scans for cash.

Over the past three years, Ilott says he has filled out hundreds of applications for jobs and has made it through several interviews. But most of the time, as soon as the employer learned of his past, he was shown the door.

“People like to present themselves in a most favorable light, but saying you’re a pedophile is not a very endearing thing,” he said. “When you know how people are going to act, you don’t even want to dress up and go to an interview.”

Ilott was hired for a few jobs, but they didn’t last long.

The day he started a position at a telemarketing firm in Somerville, someone posted a clip from a local newspaper about where Level 3 offenders in the area lived, he says. He left a few days later. One job lasted just an hour and 10 minutes. Hired as a bookkeeper for a drug rehabilitation clinic in Brookline, he lost the job after he informed local police of his new work address. An officer at the station told him, “I’m going to call your employer and plaster your picture all over the place,” he said.

When Ilott succeed in landing an interview for a job as a case manager at a substance-abuse program in Boston, he found himself sitting in a room full of children’s toys. “As soon as we learned about his background, there was no way he could work for us,” said Loretta Leverett, operations manager of the STEP Program, who interviewed Ilott. “By law, we’re unable to hire anyone with his background.”

What Ilott really wants to do is help educate people about sex offenders, which he has done twice at seminars for officers at the Boston Police Department.

Sergeant Detective Kim Gaddy, who organized the seminars for rape investigators, said she has no sympathy for Ilott’s crimes, but she described him as “forthright” about his addiction and “genuine” about wanting to do something positive.

“We want to protect the public as much as possible, but it doesn’t help when he meets opposition at every corner and constantly confronts negativity,” she said. “Either keep him in jail or give him an opportunity to be a productive citizen – you can’t have it both ways. It’s commonsense that sex offenders will likely re-offend without jobs.”

For now, with only a can of pennies to his name, Ilott’s future is hazy.

Officials at the St. Francis House have told him he’ll soon have to leave his “transitional housing” there, he said, because since Jan. 1 he hasn’t paid the $60 a week they require of residents. Without much hope for a job – he often spends several hours a day searching and applying for jobs he finds posted online, he says – he’s not sure what to do.

“I’d much prefer every employer know I’m a sex offender, but that’s not always a real option,” he said. “There’s too much of a stigma.”

So he says he sees only two unappealing options: omit parts of his background, or lie.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.